Where Worlds Collide

Picture this. A seven-year-old child is taken from her home in Germany by her mother, who returns to her family in Türkiye, without the father’s consent.

[1] The father, still in Berlin, files an application under the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction 1980, and the return proceedings begin.[3]

Yet, behind these legal mechanisms of juggling with parents thousands of kilometers apart, strict deadlines, lawyers, legal systems, lies a force which often fuels conflict but can also become the key to its resolution, namely, culture.[4] What seems like a purely legal dispute becomes a clash of assumptions about parenting, clash of values, authority, and the child’s best interests. Here, mediation, encouraged by Brussels II Regulation and the Guide to Good Practices under Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction 1980,[5] emerges not only as a complement to litigation but as a tool where cultural sensitivity is a skill essential to the resolution itself.[6]

Culture, defined by some as the ‘total accumulation of an identifiable group’s beliefs, norms, activities, institutions, and communication patterns’,[7] is an important factor in cross-border cases.[8] The bigger the cultural divide, the greater the potential for misunderstanding and conflict. Cultural expectations about family life often shape how people communicate, raise children, express emotions, interpret justice, assign gender roles, and relate to authority.[9] Parents from different backgrounds may thus enter the mediation with conflicting goals, making cultural awareness essential.[10]The Hague Conference on Private International Law in its report titled Guide to Good Practices under Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction 1980,[11] also emphasizes the importance of culture in international family mediation.[12] There it is also highlighted that mediators in such cases should have a good understanding of the cultures of the parties and should go to specific training for that.[13]

While mediators cannot be experts in every culture, and should avoid stereotyping, particularly in an era where the modern world blurs cultural distinctions,[14] they should recognise that culture can be the key to resolving conflicts.[15]

Cultural Dimensions Mediators Should Weigh: Hofstede’s Model

*Here, it is important to note that those factors below should be used as lenses which are helpful as a starting point to understand culture, and never boxes to put people in.

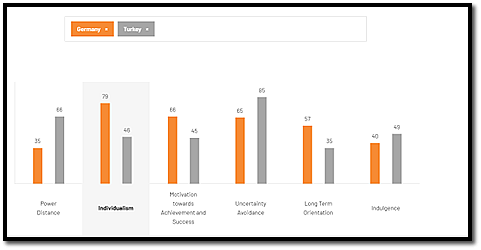

In international child abduction mediation, the cultural dimensions outlined below can help mediators tailor their approach accordingly. Though not exhaustive,[16] these categories are based on Prof. Geert Hofstede’s well-known ’Dimensions of Culture’ model, often used to understand key differences across cultures.[17] Mediators could use the ’Country Comparison Tool’[18] which is based on Hofstede’s model to analyse the dimensions for all countries.

Prof. Geert Hofstede

Source: Maastricht University (In Memoriam Geert Hofstede (1928-2020) - News - Maastricht University)

- First Dimension: Individualism/ Collectivism

- Second Dimension: Power Distance

- Third Dimension: Femininity/ Masculinity

- Fourth Dimension: Uncertainty Avoidance

- Fifth Dimension: Long Term Orientation

This dimension showcases the extent to which individuals and the group are integrated within societies.[19] In individualist cultures, like Western Europe or North America, people tend to value personal autonomy and rights.[20] When dealing with such cultures, a mediator can engage a parent in acts that are appealing to the parent’s self- sufficiency in completing tasks. In contrast, collectivist cultures, emphasize on close ties between individuals.[21] Decisions can be often made with the consideration of extended family, and a mediator aware of this difference can reframe disputes, and instead of focusing on individual rights, they could highlight shared family goals.

This dimension is about how societies handle inequalities and hierarchy.[22] Cultures which have high power distances tend to be more respectful and expected to lead towards authority figures such as the elderly and even the mediator.[23] On the contrary, parties from low-power distance cultures would expect equality and a mediator which facilitates. [24] Recognising this distinction is crucial for mediators, as in hierarchical scenarios a more structured approach can foster trust, while low-power distance settings, a collaborative approach may be more effective.

This dimension examines whether a culture reinforces more cooperative and nurturing values (feminine) or competitive, achievement-oriented ones.[25]In ‘masculine’ cultures parents may focus on asserting rights and demonstrating control over decisions, while in more ‘feminine’ cultures parents may prioritize harmony and the emotional stability of the child, which is crucial for mediators to understand.[26]

This dimension measures a culture’s comfort with ambiguity and risk.[27] In cultures that have high uncertainty-avoidance levels, usually structure and detailed agreements are preferred.[28] In low uncertainty-avoidance cultures, on the contrary, trust plays a bigger role, and rigidity may feel unnatural.[29] Knowing the differentiation of this dimension, mediators can adapt their methods by facilitating agreements with clear procedural structures that have flexibility clauses. For instance, scheduled reviews for parenting plans as the child’s needs evolve in time.

This dimension is about whether a culture is focused on the future and its stability rather than on immediate results, like short-term oriented societies.[30] The latter emphasise quick results.[31] In international-child abduction cases, this dimension can be one of the key factors for influencing the parent’s goals. This is because long-term oriented parents could emphasise gradual transitions and educational stability for the child, while short-term oriented parents may focus on the immediate return deadlines.

Using the ‘Country Comparison Tool’,[32] mediators in such cases can analyse all of those dimensions for all the countries, including other dimensions not discussed in this post.

Here is an example of the comparison between Germany and Türkiye.

You can see an example below. [33]

TOOLKIT FOR MEDIATING ACROSS CULTURES: INTERNATIONAL CHILD ABDUCTION

Given now the importance of culture and its dimensions, this section presents a set of non-exhaustive tools which mediators could use to better navigate cultural differences in international child abduction mediation sessions and turn those differences into advantages.

- Pre- Mediation Preparation: Educate yourself on the family’s cultural backgrounds before the mediation begins. Use tools such as Hofstede’s cultural dimensions or the ‘Country Comparison Tool’. It is very important not to stereotype and remain open to each family’s unique mix of values.[34] That is why initiatives such as the iCare2 pre-mediation desks in each country are so important in cases of international child abduction as they could analyse the culture of the parents there too.

- Building Trust: It is very important for parents to trust the mediator in such scenarios. Nonetheless, trust is built differently in different cultures. For instance, in some cultures sharing a coffee at the start before beginning with mediation and having an informal conversation is considered more respectful rather than diving straight into ‘business’ which might seem cold. Nonetheless, in other cultures, trust is earned by displaying competence and neutrality.[35] A culturally sensitive mediator should pay attention to those cues.

- Co- Mediation/ Bi-national mediation: Using two mediators can be especially effective in international child abduction cases.[36] When two mediators jointly facilitate a case in such cases they complement each other in gender, language, and professional experience. For instance, they could complement each other in nationality, gender, language, and professional background. If one mediator speaks the language of the parent’s and understand their cultural idioms, the other mediator may do the same for the left-behind parent’s culture. This has also been referred to as ‘bi-national mediation’ which refers to having two mediators co-mediate from the two States concerned with each knowledgeable of the other culture.[37] This model is successfully followed specifically in international child abduction cases.[38] This structure could allow each parent to feel equally represented and understood and strengthens communication across culture.Here, it is important to mention that mediators are neutral and impartial even in such cases.[39]

- Cultural Translators or Qualified Interpreters: Even when a solo mediator is used, they might bring in a cultural consultant behind the scenes or make use of community resources. For instance, a local cultural center can be consulted with the parties’ consent.

- Adaptive Process: Cultural sensitivity may mean altering the standard mediation format. A few examples: If direct joint sessions are too confrontational for one culture, the mediator might do more caucusing (separate meetings) initially and then bring the parents together at critical points if face-to-face dialogue is culturally important to the other. In addition to that, the timing of the procedure can be adjusted, as in some cultures decisions take time and rushing is not considered as good. On the contrary, when fast resolution is valued in some cultures, then the mediator can schedule accordingly. In the mediation procedure even the seating arrangements in such case could matter. For example, some cultures prefer not to sit face-to-face in adversarial posture, so circular or side-by-side seating might defuse perceived hostility.

Where Worlds Meet:

Let's imagine an example from the introduction of this post. The case exposed a cultural contrast between the Turkish mother (high power distance, collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and short-term oriented culture),[40] and the German father (lower power distance, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, long-term oriented culture).[41] In Turkish culture this would mean that typically stability comes from close family ties, so the mother in the case saw moving back to Türkiye as securing moral and emotional support. In Germany, on the other hand, considering its cultural dimensions, parenting is shared and guided by rules. For this case it was decided that the process will be a bilingual co-mediation led by a German lawyer mediation and a Turkish psychologist, which mediators balance authority and participation. Following the mediation, the agreement showcases the blended cultures: namely, that the child returns to Germany and attends a German Turkish school, spends summers in Türkiye and maintains a strong family contract. Furthermore, legal mirror orders meet the father’s needs for certainty, while the ongoing family meetings upheld the collectivist cultural values of the mother.

Culture is a powerful factor in international child abduction mediation, shaping every stage of the process, from communication to the settlement design, even if it could be a challenge for mediators to find a balance between two cultures.[42]

Culture should be approached with sensitivity and awareness, rather than a source of stereotyping or bias.

[1] HCCH, ‘Authorities. 28: Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction’ (HCHH, 2025)

Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (adopted 25 October 1980, entered into force 1 December 1983).

[3] Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (adopted 25 October 1980, entered into force 1 December 1983), Chapter III.

[4] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 555.

[5] Council Regulation (EU) 2019/1111 of 25 June 2019 on jurisdiction, the recognition and enforcement of decisions in matrimonial matters and the matters of parental responsibility, and on international child abduction (recast) [2019] OJ L 178, recital 43. See also HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 12.

[6] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 555.

[7] Carley H. Dodd, Dynamics of intercultural communication (Madison, Wis Brown& Benchmark 1995).

[8] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 12.

[9] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 558.

[10] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 555.

[11] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025.

[12] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 26.

[13] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 31

[14] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 558.

[15] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 558.

[16] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[17] Geert Hofstede, Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (Sage Publications 2001).

[18] The Culture Factor Group, ‘Country Comparison Tool’ (The Culture Factor Group, 2025) < https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool> accessed on 6 November 2025.

[19] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[20] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[21] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[22] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[23] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[24] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321.

[25] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321-322.

[26] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 321- 322.

[27] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 322.

[28] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 322.

[29] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 322.

[30] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 322.

[31] Joel Lee, ‘Culture and its importance in Mediation’ [2016] v 16 n 2 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 322.

[32] The Culture Factor Group, ‘Country Comparison Tool’ (The Culture Factor Group, 2025) < https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool> accessed on 6 November 2025.

[33] The Culture Factor Group, ‘Country Comparison Tool’ (The Culture Factor Group, 2025) < https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool> accessed on 6 November 2025.

[34] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 575.

[35] Melissa A. Kucinski, ‘Culture in International Parental Kidnapping Mediations’ [2009] v 9 n 3 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, p. 562.

[36] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 32.

[37] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 32.

[38] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 32.

[39] HCCH, ‘Guide to Good Practice under the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction: Mediation’ (HCCH, 2012) <d09b5e94-64b4-4afe-8ee1-ab97c98daa33.pdf > accessed 6 November 2025, p. 32.

[40] The Culture Factor Group, ‘Country Comparison Tool’ (The Culture Factor Group, 2025) < https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool> accessed on 6 November 2025.

[41] The Culture Factor Group, ‘Country Comparison Tool’ (The Culture Factor Group, 2025) < https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool> accessed on 6 November 2025.

[42] Martín Nuria González, ‘International parental child abduction and mediation’ [2015] v 15 n 1 Anuario Mexicano de Derecho Internacional, p. 389.