Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market and why it “broke” the Internet

Author: Petya Peteva, Legal Project Expert at Law and Internet Foundation

Introduction

The debate around the right to freedom of expression on the one hand, and the right to have your own work protected and receive revenue from it on the other is not a new one. The EU framework on copyright is extensive, including 11 Directives, 2 Regulations[1] and abundant case law. However, the Digital Age and the Digital Single Market, introduced by the “Europe 2020” strategy (and more precisely through “A Digital Agenda for Europe”) have created new issues in regard to sharing others’ own intellectual creations. While, through the introduction of a Digital Single Market, the EU aimed at expanding the four freedoms of the internal market to the digital environment and in the context of new and developing technologies (IoT, Big Data and AI)[3], it has since become clear that, in order to have a fully available online market, new rules on copyright-protected works must be introduced.[4]

To this end, a new Directive (EU) 2019/790 on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market (DSM Directive)[5]was introduced on the EU arena almost two decades after the last update on EU copyright law. While the new DSM Directive contains various provisions that have given rise to multiple debates, arguably the most controversial one is Article 17 “Use of protected content by online content-sharing service providers”. For this reason, the present blog post will have its focus on it, delving into whether it constitutes the end of free speech, as speculated, as well as what we can expect from it after it has been implemented into national legislation.

The legal landscape prior to the DSM Directive

As mentioned above, copyright has been partly harmonized at a European level with the Information Society Directive (Directive 2011/29/EC) being enacted in 2001 in order to provide for minimum common standards for the rightholders of copyright, in the context of the developing Information Society. However, with the advance of new technological developments and the overall landscape where online content is shared being transformed, it has been agreed by a general consensus that this piece of legislation is no longer up-to-date. Indeed, the digital age has drastically changed the way content circulates the online environment and it has even given rise to completely new types of such content, thus the need for a revised legal framework has been obvious for sometime now. The DSM Directive was thus adopted in 2018 and Member States were given 2 years for implementation into national legislation, with the deadline for its transposition set for 7th June 2021.

The new Article 17 - what it is and what we can expect from it

Article 17 of the DSM Directive covers the use of copyright-protected content by online content-sharing service providers (OCSSPs) and, more specifically, whenever a provider “performs an act of communication to the public or an act of making available to the public” of such protected works (Article 17(1)). For the purposes of better understanding, the definition given by the Directive under Article 2(6) of OCSSPs states that:

“‘online content-sharing service provider’ means a provider of an information society service of which the main or one of the main purposes is to store and give the public access to a large amount of copyright-protected works or other protected subject matter uploaded by its users, which it organises and promotes for profit-making purposes.”

While it remains to be further clarified what would constitute “a large amount” of such copyright-protected works, for example, it is clear that this definition is aimed at inevitably including tech giants, such as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok, to name a few, which-due to their global reach-undoubtedly fall under its scope. The Directive, in its Article 2(6), also sets out a non-exhaustive list of excluded service providers, such as not-for-profit online encyclopaedias (including Wikipedia), educational and scientific repositories, open-source platforms, online marketplaces etc. All in all, Recital 63 clarifies that whether a service provider falls within the scope of the provision is to be decided on a case-by-case basis.

It is also important to clarify from the outset that liability of OCSSPs under Article 17 does not presuppose the existence of such a liability under Article 3 of the InfoSoc Directive as well – indeed, while the latter grants authors of copyright “the exclusive right to authorise or prohibit any communication to the public of their works”, it doesn’t create explicit liability for OCSSPs per se, which is why the European Commission’s guidance on Article 17 qualifies it as lex specialis to Article 3[6]. This was also confirmed in the opinion of the Attorney General in the cases of Youtube/Cyando which stated that the online platforms in question are not to be held responsible for having communicated content to the public as it was the users of the platforms that had generated it. [7] Of course, such a liability will exist under Article 17 of the new Directive unless the OCSSPs have obtained the appropriate authorisation, however the provision cannot be applied retroactively in the above-mentioned cases. Also, Recital 64 of the DSM Directive clarifies that the right to communication to the public and the right of making available to the public as under Article 3 of the InfoSoc Directive could still be exercised by other service providers.[8]

But what does Article 17 itself entail exactly, and for whom?

By interpreting its provisions, it is evident that the Article’s primary aim is to switch liability from the users of copyrighted content to the online platforms themselves, where such content is shared and accessed. This is indeed a major development in the legal landscape as, up until now, users were solely responsible for the content they uploaded online, with service providers having limited liability - only required to take down specific content once they have been duly notified.[9] By shifting responsibility to OCSSPs, the Article practically requires them to monitor all content uploaded on their platforms in order to oversee whether it infringes copyright laws. Through such an ambitious endeavour, the Article strives towards providing better protection to the rightsholders of their protected content, which is often being monetized on, especially by the biggest OCSSPs on the market, however without providing the rightsholders themselves with any revenue. This is further strengthened by Article 17(3) which specifies that the “safe harbour” principle[10] shall not apply to situations covered by the DSM Directive.

Article 17(1) requires from the service providers to either obtain authorisation, for instance a license, from the rightsholders or the former will be held liable under the Directive for unauthorised acts that constitute communication to the public or making available to the public. It is important to state that once an authorisation has been obtained, it “shall also cover acts carried out by the users” (Article 17(2)) if the use is either non-commercial or no significant revenue is earned.

Still, the requirement under Article 17(1) is not entirely unconditional as Article 17(4) exempts service providers from liability if the following three conditions are cumulatively met, namely the OCSSP must have:

“(a) made best efforts to obtain an authorisation, and

(b) made, in accordance with high industry standards of professional diligence, best efforts to ensure the unavailability of specific works and other subject matter for which the rightholders have provided the service providers with the relevant and necessary information; and in any event

(c) acted expeditiously, upon receiving a sufficiently substantiated notice from the rightholders, to disable access to, or to remove from their websites, the notified works or other subject matter, and made best efforts to prevent their future uploads in accordance with point (b).”

Article 17(6) goes on to further specify when all of these provisions apply as it is more lenient towards new OCSSPs that have entered the market less than 3 years ago and with an annual turnover below EUR 10 million in which case only the first and the third conditions apply (albeit only the first part of Article 17(c)).

Nevertheless, we can notice multiple potential issues from the outset that may arise in the application of Article 17.

While Article 17(8) of the DSM Directive and Article 15(1) of the e-Commerce Directive[11] expressly state that “the application of this Article shall not lead to any general monitoring obligation”, also confirmed in the Sabam v Netlog[12] case, it is indeed difficult for OCSSPs to evade this given the sheer amount of online content uploaded on a daily basis nowadays, and it is more likely than not for them to become “web police officers” instead.[13] For this reason, heated discussions on the introduction of content filtering systems have been taking place and, even though the requirement for an ‘upload filter’ is nowhere expressly stated within the Directive itself, it has been generally assumed that such filters would indeed be required to comply with the legislation in question.

The introduction of these filtering systems immediately begs a second question, namely how will they comply with the exceptions under Article 17(7) – allowing copyrighted content to be used for the purposes of quotation, criticism, review, caricature, parody and pastiche? Following this, it is interesting to note that, while the Information Society (InfoSoc) Directive[14], provided its exceptions and derogations almost all optional, the new DSM Directive makes exceptions mandatory, as clarified under Recital 70. Indeed, it will be very difficult operationally for any system, following the current level of technological development, to be able to sift through such an enormous amount of online content and correctly distinguish between copyrighted material, and material that is not protected or is subject to a certain exception. This is also one of the reasons why Article 17 has been nicknamed the ‘meme ban‘, and lengthy talks have taken place on the implications for human rights that such filtering systems may pose, which will be discussed in more detail below.

A third concern is related to the role of the major OCSSPs – while one of the aims of the Directive is to achieve fair competition (Recital 1) and to establish “a well-functioning and fair marketplace for copyright” (Recital 3) at EU level, the risk of achieving the opposite effect may materialise. In fact, the requirement for monitoring of content may end up being to the benefit of the ‘giant’ service providers and can lead to the development of a monopoly. For example, YouTube has invested $100 plus million in its content filtering system since its inception with its Content ID. The purpose of the system is precisely to identify copyrighted content and provide for the next appropriate action steps.[15] However, OCSSPs that may not have the sufficient means to invest such a large sum in similar filters with such sophisticated technology would be at a considerable disadvantage and, while the Directive provides for lesser restrictions in terms of start-ups, the medium OCSSPs will practically be pushed out of the market.

Article 17 and Fundamental Human Rights

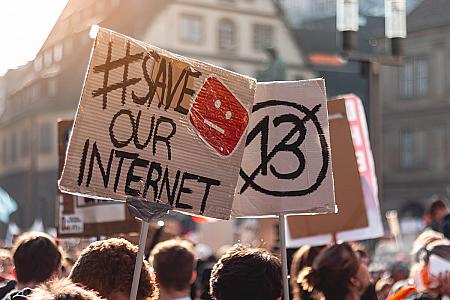

There have been major protests regarding the implementation of the DSM Directive in Finland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands and Poland[16], and 5 million signatures have been gathered against it.[17] Additionally, the Polish government has brough an action for annulment ofArticle 17 – specifically Article 17(4)(b) and (c) - based on the claim that the provision is not in accordance with the human rights framework, under the case of Poland v. Parliament and Council[18]. Could it therefore be said that the Article to filter the Internet actually ‘broke the Internet’? And should we be worried that Article 17 would mean the end of freedom of speech and the establishment of censorship?

First of all, it is of primary importance that Article 17 is interpreted in light of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (the Charter) and the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) since filtering has the real possibility of over-blocking and thus limiting the users’ freedom of expression and information (Art.11 of the Charter and Art.10 ECHR), as well as preventing them from showcasing their creativity[19], all of which is contrary to what is stated under Recital 85 of the DSM Directive, which promotes respect for fundamental rights. Indeed, Geiger and Jutte[20] show the possibility of fundamental rights being disproportionately infringed if “overly strict and broad enforcement mechanisms” are applied. They also mention the possibility of a potential infringement of the freedom to conduct a business[21], respect for private and family life[22], protection of personal data[23] and the right to property[24]. Therefore, it is of primary importance to pay heed to the mandatory exceptions (Article 17(7)) which have a very strong human rights’ basis and may be swept by filtering technology, and while memes and GIFs have been expressly excluded under the Directive[25], the implementing EU members must ensure that this remains the case in practice as well.

What the European Commission’s much anticipated guidance on Article 17[26] has shown us, however (and only three days before the official deadline for implementation), is backtracking on its initial stance that only content that is “manifestly infringing” could be subject to automated blocking[27], and has now specified in its Communication that, even if not “manifestly infringing”, any content that is “earmarked by the relevant rightholders as content whose availability could cause significant harm to them”, will be blocked. It requires “particular care and diligence” from service providers, and it specifies the need to carry out “a rapid ex ante human review” in regard to the upload of such content (particularly such which is time-sensitive). While the guidance attempts to limit this provision to only content that poses “high risks of significant economic harm”, this has a high chance of practically depriving users of all safeguards provided under Article 17 (4) and grants the copyright holders with wide discretion.[28] We can see how restrictive this may become in practice, given that rightholders may consider that almost any content could cause such a “significant harm” and indeed there have been criticisms regarding this last-minute inclusion, particularly due to the lack of transparency in taking this decision. Furthermore, claims that economic interests have been deemed a higher priority than human rights[29] have also been voiced, although Recital 70 requires to strike the right balance between human rights and intellectual property. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether this will be the final outcome, since the guidance also states that its contents might be subject to review after the judgment in Poland v. Parliament and Council becomes available.

Implementation of the DSM Directive at a national level

As it can be imagined, it hasn’t been smooth sailing for the different EU Member States to implement the DSM Directive into national legislation, and most have failed to do so before the stated deadline[30]. This can be also attributed to lack of timely provided guidance in respect to Article 17 by the EU Commission, including a postponed opinion by the Attorney General on the Polish case mentioned above.[31] This has resulted in only two countries – namely Hungary and the Netherlands – that have transposed and implemented fully the Directive in practice.[32] It has even been stated that EU countries have divided into ’originalists’ and ‘textualists‘ camps - the former making compromises with users’ safeguards and the latter putting the emphasis on them[33]. The former, such as France has decided to completely ‘ignore’ the user safeguards provided in the Directive[34] and, while France has stated that this will be a temporary measure with the redress mechanism under Article 17(9) being sufficient for users to seek their fundamental rights after the fact, the lack of support for this approach is palpable.[35] The latter on the other hand, such as Germany, has decided to take the opposite direction and has included the above-mentioned exceptions, while also introducing the so-called ‘pre-flagging’ (or ex ante) mechanism which would allow users to mark content prior to its posting on a platform as legitimate.[36] Whether this will work as effectively in practice as it does on paper remains yet to be seen, however.

Conclusion

The introduction of the Directive on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market has certainly caused a significant amount of controversy on both the legal and the political front, especially with its Article 17 imposing much higher liability to OCSSPs in regards to copyrighted content on their platforms. The debate around the incorporation of the so-called ‘content filters‘ has led to justifiable concerns that they may potentially infringe upon users’ human rights and impose Internet censorship. The recent guidance by the European Commission on the implementation of Article 17 has also been rather disappointing in terms of ensuring human rights’ protection as it seems to have shifted its stance from its previous guidance, which was based on stakeholder dialogue. With the deadline for implementation already passed and considerable uncertainty still remaining at a national level, all eyes are now on the decision from the Polish challenge to Article 17 and whether we will be able to find a compromise that will both ensure better copyright protection and compliance with fundamental rights.

[1]European Commission, ‘The EU copyright legislation https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/copyright-legislation accessed 06.06.2021.

Federico Ferri, ‘The dark side(s) of the EU Directive on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market’ (2020) China-EU Law Journal https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12689-020-00089-5#Fn1 accessed 06.06.2021.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC, OJ L 130.

[6] European Commission, ‘Guidance on Article 17 of Directive 2019/790 on Copyright in the Digital Single Market’ https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/guidance-article-17-directive-2019790-copyright-digital-single-marketaccessed 07.06.2021.

[7] Eleonora Rosati, ‘Five considerations for the transposition and application of Article 17 of the

DSM Directive’(2021) 16(3) Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice < https://academic.oup.com/jiplp/article-abstract/16/3/265/6157786?redirectedFrom=fulltext> accessed 06.06.2021.

[8] Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC, OJ L 130, recital 64.

[9] Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market ('Directive on electronic commerce')OJ L 178, Article 14.

[10]The principle of “safe harbour” is one “under which online intermediaries who host or transmit content provided by a third party are exempt from liability unless they are aware of the illegality and are not acting adequately to stop it” (Tambiama Madiega, ‘Reform of the EU liability regime for online intermediaries’ (2020) European Parliament https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2020/649404/EPRS_IDA(2020)649404_EN.pdf accessed 07.06.2021). “Safe harbours” are provided under Article 12, Article 13 and Article 14 of Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market ('Directive on electronic commerce') OJ L 178.

[11] Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market ('Directive on electronic commerce') OJ L 178, Article 15(1).

[12] Case C-360/10 SABAM v. Netlog [2012] EU:C:2012:85.

[13] Federico Ferri, ‘The dark side(s) of the EU Directive on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market’ (2020) China-EU Law Journal https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12689-020-00089-5#Fn1 accessed 06.06.2021.

[14] Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society, OJ L 167.

[15] Paul Sawers, ‘YouTube: We’ve invested $100 million in Content ID and paid over $3 billion to rightsholders’ (2018) VentureBeat https://venturebeat.com/2018/11/07/youtube-weve-invested-100-million-in-content-id-and-paid-over-3-billion-to-rightsholders/ accessed 06.06.2021.

[16] Council of the European Union, Joint statement by the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Poland, Italy and Finland (2019) 2016/0280(COD) https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7986-2019-ADD-1/en/pdf accessed 06.06.2021.

[17] Laura Morelli, ‚EU Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market: New Liability for Online Content-Sharing Service Providers’ (2019) Lexology <https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=f4e42cca-328f-4ba3-ad46-657b4c9395a6> accessed 06.06.2021.

[18] Case C-401/19: Action brought on 24 May 2019 — Republic of Poland v European Parliament and Council of the European Union OJ C 270, 12.8.2019.

[19] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2012/C 326/02), Article 13.

[20] Geiger, Christophe and Jütte, Bernd Justin, ‘Platform liability under Article 17 of the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive, Automated Filtering and Fundamental Rights: An Impossible Match’ (2021) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3776267 accessed 06.06.2021.

[21] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2012/C 326/02), Article 16.

[22] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union(2012/C 326/02), Article 7.

[23] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2012/C 326/02), Article 8.

[24] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2012/C 326/02), Article 17.

[25]European Parliament, Agreement reached on digital copyright rules (2019) https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20190212IPR26152/agreement-reached-on-digital-copyright-rules accessed 06.06.2021.

[26] European Commission, ‘Guidance on Article 17 of Directive 2019/790 on Copyright in the Digital Single Market’ https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/guidance-article-17-directive-2019790-copyright-digital-single-market accessed 07.06.2021.

[27] European Commission, Targeted consultation addressed to the participants to the stakeholder dialogue on Article 17 of the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market https://www.communia-association.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/200727EU-targetted_consultation_art17shd.pdf accessed 06.06.2021.

[28] Julia Reda and Paul Keller, ‘European Commission back-tracks on user rights in Article 17 Guidance’ (2021) Kluwer Copyright Blog http://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2021/06/04/european-commission-back-tracks-on-user-rights-in-article-17-guidance/ accessed 06.06.2021.

[29] Thomas Lohninger, ‚’European Commission ignores civil society concerns and sides with entertainment industries’ (2021) Epicenter.works https://en.epicenter.works/content/european-commission-ignores-civil-society-concerns-and-sides-with-entertainment-industries accessed 06.06.2021.

[30] Communia Association, ‘DSM Directive implementation update: With one month to go it is clear that the Commission has failed to deliver’ (2021) COMMUNIA https://www.communia-association.org/2021/05/07/dsm-directive-implementation-update-with-one-month-to-go-it-is-clear-that-the-commission-has-failed-to-deliver/ accessed 07.06.2021.

[31] Paul Keller, ‘It’s 23 April 2021, so where is the Advocate General opinion in Case C-401/19 Poland v Parliament and Council?’ (2021) Kluwer Copyright Blog http://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2021/04/23/its-23-april-2021-so-where-is-the-advocate-general-opinion-in-case-c-401-19-poland-v-parliament-and-council/ accessed 07.06.2021.

[32] Chiara Horgan, ‘Member States make slow progress on DSM Directive as deadline looms’ (2021) Lexology https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=88aa5381-11e8-4433-9e76-08532b4340e5 accessed 07.06.2021.

[33] Paul Keller, ‘Divergence instead of guidance: the Article 17 implementation discussion in 2020 – Part 2’ (2021) Kluwer Copyright Blog http://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2021/01/22/divergence-instead-of-guidance-the-article-17-implementation-discussion-in-2020-part-2/ accessed 07.06.2021.

[34] Communia Associaton, ‘France once more fails to demonstrate support for its interpretation of Article 17’ (2021) COMMUNIA https://www.communia-association.org/2021/02/04/france-once-more-fails-to-demonstrate-support-for-its-interpretation-of-article-17/ accessed 07.06.2021.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Gregor Schmid and Malek Barudi, ‘Update Copyright in the Digital Single Market: On the implementation of the DSM Copyright Directive in Germany’, TaylorWessing https://iot.taylorwessing.com/update-copyright-in-the-digital-single-market-on-the-implementation-of-the-dsm-copyright-directive-in-germany/ accessed 07.06.2021.